February 9, 2008: Colonial Coin Collecting Q & A, Part 2

Waaaaaay back in August of 2006 we wrote part 1 of this Q & A with every intention of adding Part 2 eventually. Well, as it turns out, eventually is today, and Part 2 begins right now (though we’d suggest you might want to scroll down a year and a half and check out Part 1 for a refresher first):

Q: I understand that a lot of the colonials listed in the Redbook aren’t truly “Colonial”. Should I not collect these?

A: I think it is important to make a distinction between a semantic debate over the term “Colonial”, and a more substantive discussion about which issues, if any, are not worthy of being collected.

First let’s tackle the semantic challenge.

I think the most relevant definition of Colonial (with a capital ‘C’) in this context is something like “Pertaining to the 13 British colonies that became the United States of America, or to their period.”

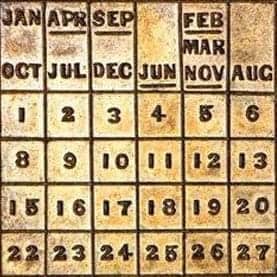

But as we touched on in Part 1, the term ‘colonial coin’ is generally used among collectors and specialists in this area as convenient shorthand for a much broader group of coins and tokens which the Redbook happens to list in 12(!) distinct categories:

- Spanish Colonial Issues

- British New World Issues

- Coinage Authorized by British Royal Patent

- Early American and Related Tokens

- French New World Issues

- Speculative Issues, Tokens, and Patterns

- Coinage of the States

- Private Tokens After Confederation

- Washington Pieces

- Continental Currency

- Nova Constellation Patterns

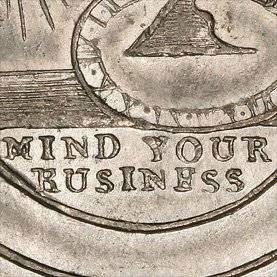

- Fugio Cents

Of the coins and tokens listed above, the earliest piece bears the date 1652, and the latest 1820 – though others were struck as early as 1616 and undated, or as late as 1850 or 1860 and backdated. Are you with me so far?

Some coins and tokens on this list were struck in early America, others in England, Ireland, France, Spain, Mexico, etc.

Some circulated in early America (but also in what is now Canada, Bermuda, the Caribbean, etc.) as money, by official decree, some informally, some perhaps not at all.

And some issues are on this list because they bear motifs or legends which have some connection (however tenuous) to early America.

And this is to say nothing of the other issues and series which are often referred to as colonial, or colonial related – including contemporary circulating counterfeits of American origin, additional foreign issues known to have circulated in early America, some medals, etc. – which aren’t in the Redbook. Yet.

In other words, these issues are not all Colonial per the normal definition of the word. But in the absence of any other convenient, universally accepted term to describe all of these diverse coins and tokens (and because reciting these 12 categories and the other unlisted items by name is fairly cumbersome), it is the best we have for now.

With that, I would suggest we put the semantic argument to bed and focus on the real question:

Which of these issues are worthy of being collected?

In order to determine that, our advice would be to forget everything we just discussed and instead think of all of these coins and tokens in four basic categories (noting that not all of us in this field will agree completely as to which issues belong in which category):

1. Issues struck in early America which circulated as money.

Examples include the Massachusetts silver issues, state coinage of Connecticut, Vermont, Massachusetts and New Jersey, Chalmers silver coinage, etc.

2. Issues imported into early America which officially circulated as money.

Examples include Maryland Lord Baltimore coinage, Virginia coinage, some of the French Colonial issues, etc.

3. Issues imported into early America which unofficially circulated as money.

Examples include the Hibernia coinage, Nova Constellatios, Bar Copper, etc.

4. Issues which exhibit some connection or relationship to early America but which were probably not intended to circulate as money (and which may not have ever been imported into early America, at least in quantity).

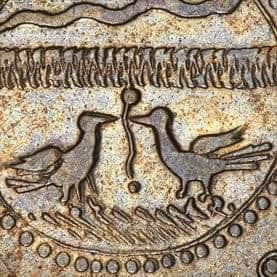

Examples include the Elephant Tokens, Franklin Press Tokens, etc.

So, are these categories meaningful to you? Do you feel that coins and tokens in some of these categories are more worthy of being in your collection than others? And I say ‘you’ because ultimately you are the only one who should decide what is interesting to you and ultimately what you want to include in your collection.

Some purist collectors choose to include only those items in the first category and collect only pieces which were struck ‘here’.

Others focus on the first two categories, adding coins and tokens struck in foreign lands which were actually authorized to be, and were used as, money in early America.

On the other hand, traditionalists (ironically) may take a more expansive view and select that which has been collected by the famous collectors of the past (including the likes of Loren Parmelee, John Story Jenks, Garrett, Norweb, Louis Eliasberg and John Ford to name a few) for the last 150 years or so. Interestingly, it is the content of past collections like these which has influenced (as much as anything else) what is included in the Redbook today.

Personally, I am a believer in collecting coins for pleasure (as opposed to some sort of attempt to create a documented and 100% verifiable history of early American financial vehicles) and would include the related issues that have colonial American relevance, that I found interesting or attractive, and that have been historically collected as part of the series. In fact, some of these ‘Category 4’ coins and tokens are among the most popular and interesting in the Redbook, and it seems a shame to dismiss them.

Which is to say that I think it is perfectly valid to include various issues for traditional, romantic and aesthetic reasons as opposed to the supposed technical reasons of which coins and tokens were officially authorized to be used here as money.

But I’m not you, and the decision is not mine to make.