September 10, 2007: So How’s the Coin Market? (Parts 1 & 2)

That’s a question dealers (including us) hear all of the time from customers.

And while responses to this question may vary wildly depending on who you ask, this is our Coin Commentary and here you will get the ‘CRO View’ (which happens to be pretty well researched).

You see, your intrepid author (Dave W.) did his undergraduate college thesis on this very subject, all those many moons ago.

I went to college right after the 1980 boom-and-bust coin market and I chose to do a study of the coin market because I wanted to know what the heck happened, and if I could possibly predict such a terrible crash in advance.

First, a Little History

For those of you who don’t go back that far in the coin hobby, there was an amazing boom in coin prices from 1979 to April of 1980. Everything – and I mean everything – was going up at a clip of about 10% a week during that period. It was simply the greatest time in history to be in the US coin market. Everyone was a stone cold genius, and even one’s coin buying ‘mistakes’ took only a week or two to turn into winners.

In April of 1980, it ended. Instantly. Not gradually and painlessly. No, it was like someone turned off a light switch. One day coins were king and cash was just little pieces of paper with writing on it. The next day it was as if someone had infected every coin with the Ebola virus. No one wanted to buy coins.

Then came the long, slow, painful slide. Coins went down in value every month after that market peak. You bought them cheaply. Then, two months later you were completely buried in them. Believe me, it seemed you had to be either very brave or very stupid to buy coins during that agonizing period.

The Bottom

We didn’t know it at the time of course, but prices were bottoming out during late 1983.

For you colonial coin fans, this roughly coincided with the sale of the Roper Collection by Stack’s. Mr. Roper passed away in early 1983, and his family quickly put his coins up for auction. The offering was nothing less than astonishing, including seven wholesome Higley coppers and superb examples of just about every single colonial rarity in existence. The coins were sold without reserves, the sale was well publicized, and all the major buyers were in attendance.

And it was a bloodbath.

The coins realized mere fractions of what they brought when Mr. Roper purchased them in the preceding years, or what they were worth just a few years later. But no one knew then that the coin market would recover.

Meanwhile, Back at the Dorm . . .

Well, I had personally been whipsawed by this coin market, and I was feeling a bit bruised. Luckily, the engineering school I went to had a very open view of what was acceptable as a thesis topic.

As I recall, the college mandated choosing a topic that would “Use Technology to Solve a Problem in Society”. The problem I chose to fix for our society was how to prevent getting one’s clock cleaned by a falling coin market. It took quite a bit of selling, but my professor eventually agreed to it.

The official title of my paper was “Building an Econometric Model to Predict Prices in the U.S. Rare Coin Market”. (One of the things I learned in school was how to use a lot of big words to make it seem like you knew what you are talking about. That works wicked good).

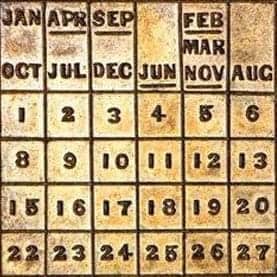

It actually was a lot of work, and took the better part of a year to put together. First I had to gather up Greysheets for the prior 20 years (better known as The Coin Dealer Newsletter, published weekly since 1963). Then I chose a representative basket of coins that were actually available for sale on the market (for example, a common date $20 Saint was chosen for the basket, whereas an 1804 Silver Dollar was not). Then I had to gather up data from the same period on every bit of economic data that I thought could possibly have an effect on rare coin prices. For example:

- Interest rates

- Precious Metal Prices

- Stock Market Indexes

- Housing Prices

- Inflation Rate

- Crude Oil Prices

- Money Supply Data

Then I had to find coin market data that was simply not available in the Greysheets. This was actually the most interesting part of the study, and the most fun. I made up a survey and sent it to about 75 of the most prominent coin dealers of the day. These were the Big Dogs of the coin market – the ones who had lived through the ups and downs of several markets.

It was a fairly long survey, with a few multiple choice questions, but mostly made up of ‘essay-type’ questions, along with an explanation from me as to why I wanted the information. It would take them each quite a while to fill it out properly.

In retrospect, it was foolhardy to expect more than a few of these top dealers to take time out from making a living in a brutally tough market to fill out some kid’s lengthy survey. But, surprisingly, well over half of the dealers I sent it to completed it and sent it back.

Many wrote long and detailed answers to my questions. Some of their responses I could have predicted, but others were quite surprising, candid and insightful.

Dave the Human Computer

I now had all of the data I needed. Mountains of it, in fact. All I had to do was analyze it.

And note that this was in the days before personal computers were commonly available to the masses. In fact, I recall that the Industrial Engineering department at my college had one ‘Apple’ computer (no, not an ‘Apple II’, but an ‘Apple’). Trouble was, only the professors were allowed to use it. (Most didn’t know how to use it anyway, so it mostly sat idle. I didn’t know how to use it either, so that fact didn’t bother me).

So there I was, doing calculations by hand, studying and re-studying the figures, assembling the data in columns on engineering-style grid paper, looking for some subtle patterns or intricate causal relationships between obscure market forces (or combinations thereof) and US coins prices.

The question I wanted to answer was (and still is): What few indicators should you focus on to be able to predict if the U.S. coin market will (1.) stay the same, (2.) get stronger, or (3.) get weaker? After many months, all that data and all that market info had been tabulated and digested, and the answer was much simpler than I thought . . .

And now we are pleased to bring you Part 2

And the Winner is . . .

When I started the project, my own personal guess was that the price of rare coins was affected primarily by two factors: the price of gold, and the inflation rate. I figured they would track exactly, and that there would be a time lag of a few weeks. It turns out that I was completely wrong.

Did coin prices follow interest rates? No.

Did they follow oil prices? Nope.

Did they follow the supply of money in circulation? Nyet.

Did they even follow the price of gold? Not really. It turns out the gold had only a very tiny influence on US coin prices, according to the numbers. That was a big surprise to me.

According to my research, the price levels of US rare coins could be predicted largely by (drum roll please) . . . watching the price of silver. During the period studied, anyway, there was about a 2 month lag in the price of that “basket” of rare coins vs. the price of an ounce of silver bullion.

At the time, silver was skyrocketing. Lots of coin dealers and collectors were taking some or all of their windfall profits in silver bullion (even scarce silver coins were often worth more as “melt value” than they were as collectables) and pouring their profits into rare coins.

There are only so many rare coins on the market at any one time. Thus, the prices of the rare coins on the market also skyrocketed. Conversely, when the silver market crashed, all of those people who made ridiculous amounts of money in silver bullion were now engaged in losing it each day as the price of silver plummeted. These people now had zero interest in buying any more rare coins. In fact, many would have liked to sell them for whatever they could get. And some did – taking huge percentage losses.

I’m not sure why the price of gold did not track US rare coin prices nearly as closely as silver did. My memory of those events was that when silver went up, gold did too. But the reality was, according to the data they followed different paths in many cases (though they obviously peaked in price at about the same time). Strange maybe, but that’s the story that the numbers told.

Yes, Dave, but what about Today’s Coin Market?

I’m going to guess that the influence of silver prices has less of an effect on the price of coins that it used to have. The boom in US coin prices from 1987-1990 occurred during a period of falling prices for both gold and silver, for example.

So what do we at the enormous Coin Rarities Online group of companies do these days to gauge the current health of the US coin market? Well, I’ll tell you what three things that I monitor:

1. Gold and silver price levels. Yes – the old standby. If you were going to choose only one thing to watch (OK, technically, two things), it would be this. If things don’t look good out there in the coin market, but the price of these two precious metals is strengthening, chances are the coin market will be fine.

2. Interest rates. I’m really not sure how well this tracks coin prices these days (it had little or no influence back in my 1963-1983 study), but logic tells me that some dealers and some collectors are borrowing money these days to buy coins, often from a home equity line of credit. Whether I think it is a good idea or not (I definitely do not) is immaterial – it is happening to some extent. If interest rates go up, it makes it less attractive to borrow money to buy coins. It also makes alternative places to park funds (such as bonds and money market accounts) more attractive.

3. How close to Greysheet “bid” prices most coins sell for at public auction. One needs to do a little work to get a feel for this. I use the Heritage Coins website (www.HA.com) because it is user friendly and has the most information in it. I choose some commonly traded coins (Saint Gaudens’ $20’s in PCGS or NGC MS-64; slightly better date Morgan Dollars, some gold commems, some common silver type coins in unc. and proof, etc.) and see how close to the published Greysheet bid levels most of them sell for.

If these items mostly sell for close to bid to over bid (as is the case at present), I don’t worry. If I check and it seems a lot of them are selling at significant discounts to Greysheet bid (20-30%), then I start to worry.

I don’t “handpick” the coins. I figure most such coins are of average or mediocre quality. If these coins are still selling for around bid or more, there is decent underlying demand. If they are selling for much less, that is a weak signal for coins.

Notice that I didn’t say anything about looking at selected “record” prices (i.e. a Buffalo nickel might sell for six times Greysheet bid at an auction, for example, and set a record price for the date. Or perhaps an 1804 Silver Dollar sets a new price record at auction). Something like this is always happening in the coin market, regardless of how strong or weak the market is. There are always a few lots in every auction whose prices amaze onlookers. I want to know what the great mass of ordinary coins is doing. Those will tell the true story.

Epilogue

Well, that’s it. You can agree or disagree with the points made above. I’m just telling you what we do here at CRO. These simple tools are far from infallible, but I think they will help you see the few things that really seem to move the coin market, and help you ignore the “tsunami” of conflicting information that is continually roaring at us.